This tutorial is an extension of my previous article, Using Passport.js and Mongoose for Local User Authentication. If you need help getting set up with local user authentication, please follow that article first.

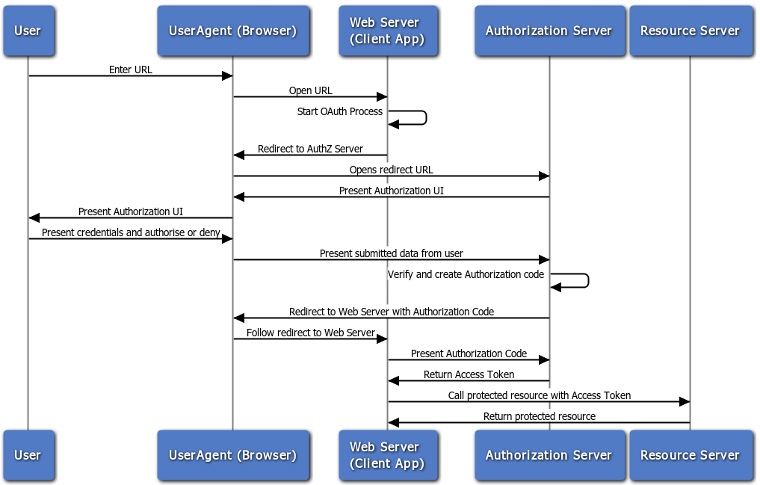

OAuth2.0 gives your app the ability to work with content producers to share content between your services and their website. Integrating OAuth2.0 opens a large range of features you can integrate into your application, including a safe way to implement authentication inside a mobile application. Rather than storing usernames and passwords, applications can store safer access codes and tokens. Before we dive in, lets take a look at how OAuth2.0 works, and how Passport.js is set up to integrate OAuth2.0.

How OAuth2.0 Works

The first step in creating an open authentication layer into your app is setting

up a zone for holding the requesting applications metadata. The primary

information you need to hold is the applications site domain for verification

of response redirect URLs, and an active/deactive switch so you can disable

offending applications easily. Other features you can implement on your own

(such as a website for developers to set up their applications on their own,

display title, etc). Next, the requesting application sends users to a specific

URL on your website that asks the user to login, and shows the user what

permissions the application is requesting. The parameters given to your

application here are the ID of the requesting application (client_id), the

permissions the application is requesting (scope), and the URL to redirect

upon completion or failure of the request (redirect_uri). This is where we’re

going to validate the apps information against our database, and make sure the

application isn’t asking for a scope we don’t support. We’ll display a login

form with a button for logging in and accepting as one action, or just an

Authorize button if they’re already signed in (similar to LinkedIn or Twitter’s

OAuth pages, if you are familiar). After our user accepts the connection, we’ll

generate and save a grant code into our database, and associate it with that

user, which contains the application and that scope. Grant codes do not have an

expiration date, however, more advanced applications give users the ability to

revoke grant codes (and in doing so, invalidate request tokens as well). We are

going to give the requesting application our grant code when we redirect them to

their redirect URI. The requesting application should save the grant code in

their database, as it will continuously be needed. Finally, the application will

request a temporary request token that expires after approximately fifteen

minutes to an hour by supplying the grant code we gave them, and a secret string

that only that applications servers should hold. The application will continue

to request these tokens as it tries to make a new request if it has no valid

request tokens. The request token is what will be sent with every API

call.

That’s it. Now we can move onto integrating this structure into our app.

Step 1: Database Schemas

To get started, we need a number of database schemas. I’m skipping much of the

verbose details about how Mongoose works, as you probably already know. We are

using the package uid2 for generating random strings. While adding

oauth_id property to our application schema is not necessary (you could use

Mongoose’s built-in Id property instead), we are using it to give integers

rather than a random string as the application’s client ID (which will be used

later). For simplicity’s sake, we’re not implementing auto-increment feature in

this tutorial—checkout

mongoose-auto-increment for details (note that field would be

oauth_id).

var uid = require('uid2');

var ApplicationSchema = new Schema({

title: { type: String, required: true },

oauth_id: { type: Number, unique: true },

oauth_secret: { type: String, unique: true, default: function() {

return uid(42);

}

},

domains: [ { type: String } ]

});

var GrantCodeSchema = new Schema({

code: { type: String, unique: true, default: function() {

return uid(24);

}

},

user: { type: Schema.Types.ObjectId, ref: 'User' },

application: { type: Schema.Types.ObjectId, ref: 'Application' },

scope: [ { type: String } ],

active: { type: Boolean, default: true }

});

var AccessTokenSchema = new Schema({

token: { type: String, unique: true, default: function() {

return uid(124);

}

},

user: { type: Schema.Types.ObjectId, ref: 'User' },

application: { type: Schema.Types.ObjectId, ref: 'Application' },

grant: { type: Schema.Types.ObjectId, ref: 'GrantCode' },

scope: [ { type: String }],

expires: { type: Date, default: function(){

var today = new Date();

var length = 60; // Length (in minutes) of our access token

return new Date(today.getTime() + length*60000);

} },

active: { type: Boolean, get: function(value) {

if (expires < new Date() || !value) {

return false;

} else {

return value;

}

}, default: true }

});

var Application = mongoose.model('Application', ApplicationSchema);

var GrantCode = mongoose.model('GrantCode', GrantCodeSchema);

var AccessToken = mongoose.model('AccessToken', AccessTokenSchema);

Step 2: Implementing oauth2orize

The creator of Passport.js also manages plugins for handling OAuth2.0

authentication, named oauth2orize. This plugin helps implement OAuth2.0 easily into your

application, however I have come to the conclusion that the documentation for

oauth2orize is somewhat complex or incomplete. The oauth2orize plugin is set

up to create a server, which is then configured for creating grant codes,

creating request tokens, and serializing/deserializing the application into a

browser session (for persisting information between multiple stages of user

login and user acceptance to the requesting application). When the application

requests a new request token from a grant code, we have to find the application

model ourselves and inject it into the req variable as req.app

(oauth2orize confusingly calls requesting applications as ‘users’, and

Passport.js is already using req.user for the actual user). We will take care

of that when we get to exchanging codes, but that is the reason for {

userProperty: 'app' } below.

var oauth2orize = require('oauth2orize');

var server = oauth2orize.createServer();

server.grant(oauth2orize.grant.code({

scopeSeparator: [ ' ', ',' ]

}, function(application, redirectURI, user, ares, done) {

var grant = new GrantCode({

application: application,

user: user,

scope: ares.scope

});

grant.save(function(error) {

done(error, error ? null : grant.code);

});

}));

server.exchange(oauth2orize.exchange.code({

userProperty: 'app'

}, function(application, code, redirectURI, done) {

GrantCode.findOne({ code: code }, function(error, grant) {

if (grant && grant.active && grant.application == application.id) {

var token = new AccessToken({

application: grant.application,

user: grant.user,

grant: grant,

scope: grant.scope

});

token.save(function(error) {

done(error, error ? null : token.token, null, error ? null : { token_type: 'standard' });

});

} else {

done(error, false);

}

});

}));

server.serializeClient(function(application, done) {

done(null, application.id);

});

server.deserializeClient(function(id, done) {

Application.findById(id, function(error, application) {

done(error, error ? null : application);

});

});

Step 3: Writing our Authentication API

Now that our oauth2orize server is set up, and we’ve already implemented

Passport.js user authentication into our app, setting up the pages for our users

to accept or deny requesting applications is going to be much easier. We’re

going to use /auth/start to start requests—this will be where requesting

applications send users, and /auth/finish will be where we check through the

request, generate grant codes, and send them back to the requesting application.

For this example, I’m going to be using the Jade templating

language. If you passed off Jade

as an ugly language before giving it a chance (like me), I highly recommend

giving it another chance, because it is the most amazing template engine I have

ever used, and plus, it is easy to integrate with Express. We also have to

listen for a URL parameter response_type, which tells our application what

type of code the application is looking for (this tutorial only has instructions

for code style grants). That parameter will need to follow the flow into the

/auth/finish request. Note that I also am allowing the domains property in

an Application include custom URL schemes (protocols), letting Applications

redirect to their URL scheme and thus pop back into the application on a mobile

device to complete the authentication (as long as that URL scheme is not http or

https).

var url = require('url');

app.get('/auth/start', server.authorize(function(applicationID, redirectURI, done) {

Application.findOne({ oauth_id: applicationID }, function(error, application) {

if (application) {

var match = false, uri = url.parse(redirectURI || '');

for (var i = 0; i < application.domains.length; i++) {

if (uri.host == application.domains[i] || (uri.protocol == application.domains[i] && uri.protocol != 'http' && uri.protocol != 'https')) {

match = true;

break;

}

}

if (match && redirectURI && redirectURI.length > 0) {

done(null, application, redirectURI);

} else {

done(new Error("You must supply a redirect_uri that is a domain or url scheme owned by your app."), false);

}

} else if (!error) {

done(new Error("There is no app with the client_id you supplied."), false);

} else {

done(error);

}

});

}), function(req, res) {

var scopeMap = {

// ... display strings for all scope variables ...

view_account: 'view your account',

edit_account: 'view and edit your account',

};

res.render('oauth', {

transaction_id: req.oauth2.transactionID,

currentURL: req.originalUrl,

response_type: req.query.response_type,

errors: req.flash('error'),

scope: req.oauth2.req.scope,

application: req.oauth2.client,

user: req.user,

map: scopeMap

});

});

app.post('/auth/finish', function(req, res, next) {

if (req.user) {

next();

} else {

passport.authenticate('local', {

session: false

}, function(error, user, info) {

if (user) {

next();

} else if (!error) {

req.flash('error', 'Your email or password was incorrect. Try again.');

res.redirect(req.body['auth_url'])

}

})(req, res, next);

}

}, server.decision(function(req, done) {

done(null, { scope: req.oauth2.req.scope });

}));

When someone requests /auth/start, we render

a page named oauth. This page displays what permissions are being requested

from the originating application, a login form if the user is not currently

logged in with an Authorize button combining the two actions, or a simple

Authorize button if they are already signed in. Here’s what the page looks like

in Jade.

.oauth-form

h1.text-center!= 'Connect with ' + application.title

form(method='post', action='/auth/finish')

input(type='hidden', name='transaction_id', value=transaction_id)

input(type='hidden', name='response_type', value=response_type)

input(type='hidden', name='client_id', value=application.oauth_id)

input(type='hidden', name='auth_url', value=currentURL)

input(type='hidden', name='scope', value=scope.join(','))

.well

p= application.title + ' requires permission to '

each item in scope

if scope.indexOf(item) == scope.length-2

!= '<strong>' + map[item] + '</strong> and '

else

if scope.indexOf(item) == scope.length-1

!= '<strong>' + map[item] + '</strong>'

else

!= '<strong>' + map[item] + '</strong>, '

| .

if user

p Click <em>Authorize</em> to allow this app to connect with your account.

else

p Sign in below to allow this app to connect with your account.

each message in errors

.alert.alert-warning

p= message

if user

.form-group.info-padded

p.text-center!= 'Signed in as <strong>' + user.name + '</strong>'

p.text-right

a(href='/logout?next=' + encodeURIComponent(currentURL))= 'Not ' + user.name + '?'

button.btn.btn-default(type='submit') Authorize →

else

.form-group

label(for='email') Email address

input.form-control#email(type='email', name='email', autofocus)

.form-group

label(for='password') Password

p.small!= 'Your password will <strong>not</strong> be shared with <strong>' + application.title + '</strong>'

input.form-control#password(type='password', name='password')

p.text-right

button.btn.btn-default(type='submit') Authorize →

Step 4: Exchanging Grant Codes for Access Tokens

Grant codes are not actually the tokens that requesting applications are going

to be using to get protected data. At this point, our server has already sent

the user back to the originating application, and now it’s up to that

application to get an access token for requesting data later. The originating

application can request new access tokens countless times in the future as its

access tokens expire or are invalidated in any way. This request is where the

applications secret key is used. The applications secret key should be protected

on the application’s server, and never exposed to users. oauth2orize expects

us to implement an entirely new authentication method for applications into

Passport.js, but personally, I believe that the Passport.js authentication

methods should be reserved for authenticating users, rather than mixing them

with methods for authenticating applications. The only benefit I see in using

Passport.js for authentication is multiple ways for an application to validate

itself. However, in number-of-lines of code and number-of-dependencies, it does

not seem very beneficial. So I am writing middleware to inject the app to the

req.app variable myself.

app.post('/auth/exchange', function(req, res, next){

var appID = req.body['client_id'];

var appSecret = req.body['client_secret'];

Application.findOne({ oauth_id: appID, oauth_secret: appSecret }, function(error, application) {

if (application) {

req.app = application;

next();

} else if (!error) {

error = new Error("There was no application with the Application ID and Secret you provided.");

next(error);

} else {

next(error);

}

});

}, server.token(), server.errorHandler());

Step 4.5: Application Integration

Applications now have complete access to authenticate users. Here is where we would write a guide for app developers about how to use our new authentication server. URLs to authentication pages can be constructed like so:

https://mycoolwebsite.com/auth/start?client_id=OAUTH_ID&response_type=code&scope

=edit_account,do_things&redirect_uri=REDIRECT_URI

When we redirect back to the applications redirect URI, we will include a

code=GRANT_CODE URL parameter, or information about why the authorization

attempt failed.

Step 5: Creating Authenticated API Endpoints

Now that our application can get a grant code and request token, we need to give that application access to some awesome protected API endpoints for actually doing cool stuff with our users and our data. While most of the actual APIs are going to be unique to you and your application, here is how we will be verifying that an applications access tokens look okay.

var PassportOAuthBearer = require('passport-http-bearer');

var accessTokenStrategy = new PassportOAuthBearer(function(token, done) {

AccessToken.findOne({ token: token }).populate('user').populate('grant').exec(function(error, token) {

if (token && token.active && token.grant.active && token.user) {

done(null, token.user, { scope: token.scope });

} else if (!error) {p

done(null, false);

} else {

done(error);

}

});

});

passport.use(accessTokenStrategy);

app.get('/api/me',

passport.authenticate('bearer', { session: false }),

function(req, res, next) {

// ... Here we can do all sorts of cool things ...

res.json(req.user);

}

);

That’s It!

Whoa. That was a lot of information to consume. But hey! You have a working application implementing user authentication, OAuth2.0 application authorization and protected API endpoints. How cool is that? If you have any questions about this article, please leave your feedback in the form below, or check out my Twitter—@hnryjms. Stay tuned for the next guide, where I show how to use Access Control to prevent applications with the wrong scope from accessing restricted API’s.